How the Netherlands Indies' stamps transformed into Indonesian ones

When rumours arose of a joint stamp issue to mark the 60th anniversary of Indonesian independence, both the Dutch and Indonesian postal authorities were quick to deny them. That was no great surprise, as the colonial period still touches a raw nerve in both countries.

The last Dutch royal visit, for example, in 1995, was fraught with politics, raising difficult questions about whether Queen Beatrix should apologise for imperialism in what was then the Netherlands Indies (or Dutch East Indies), or voice concern over present-day Indonesia’s poor human rights record.

It’s the classic trauma that results from colonial history, but the transition to independence was far more painful.

Imperialism & nationalism

At the start of the 20th century, Dutch colonial activities were limited to the main western islands of the Netherlands Indies: Borneo, Java and parts of Sumatra. But the next decade saw their influence expanded to the outlying islands.

As elsewhere, this expansionism was driven by a hunger for natural resources, and it wasn’t long before the Indies were coughing up 14% of the Netherlands’ national income.

With rampant imperialism came brute force, and the Aceh War in northern Sumatra, which had been raging ever since the 1880s, was brought to a successful conclusion in 1904.

Native nationalism, however, was growing rather than waning, and Japan’s shock military victory over Russia in 1905 demonstrated for the first time that an Asian country could stand up to European power.

May 23, 1908, saw the founding of the first Indonesian political party, the Boedi Oetomo, and that date is still celebrated as Indonesia’s national day.

In the motherland, too, a wind of change was starting to blow. Reports of atrocities in the Indies fuelled calls for a more ethical colonial policy.

When the first Indonesian mass movement based on religion, Sarekat Islam, came to prominence, the Dutch decided not to boost its popularity by trying to suppress it.

However, when Kusno Sosrodihardjo, better known as Sukarno, formed the radical Partai Nasional Indonesia, refusing to cooperate with colonial rule, the string of liberal governors was ended by the appointment of hard-liners, and the rift deepened.

Stamps up to 1941

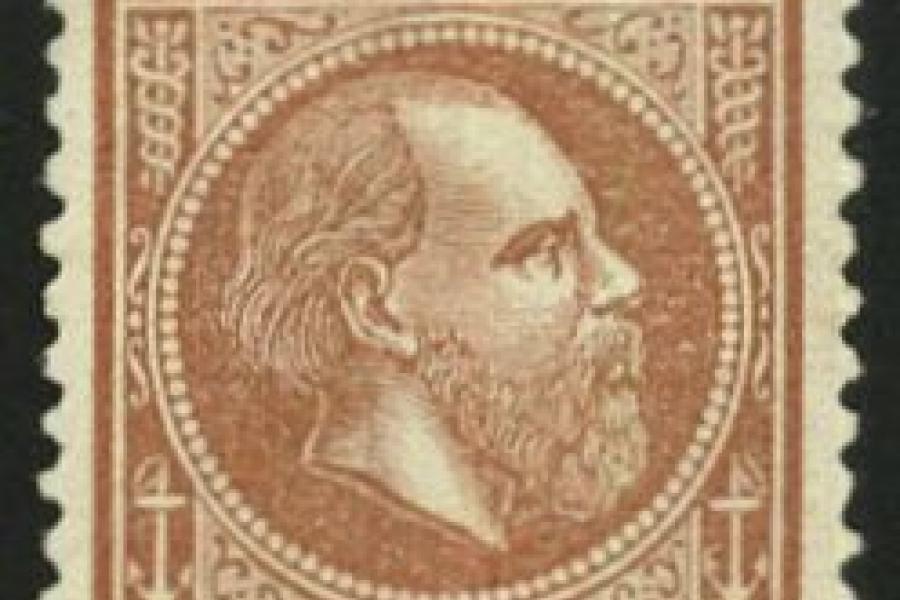

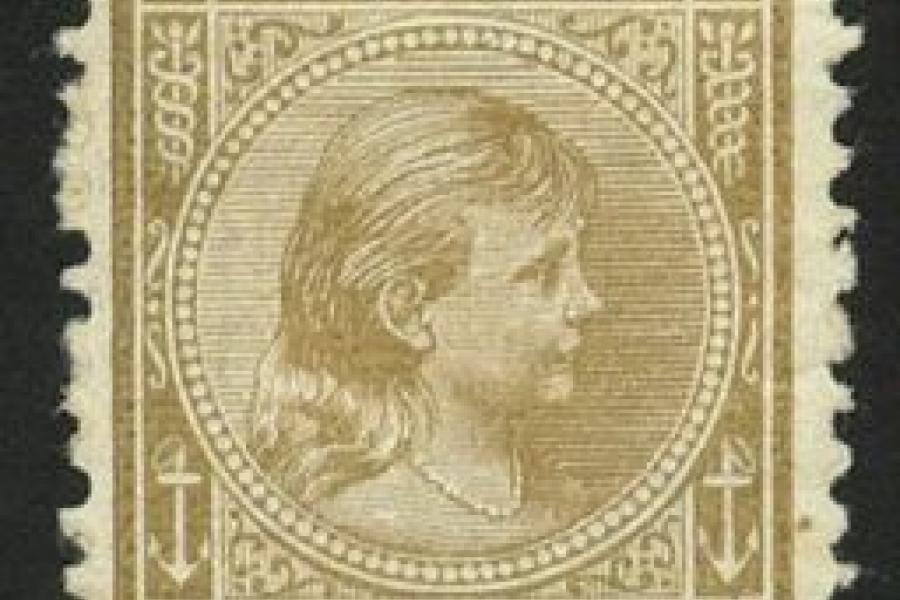

The first Netherlands Indies stamps had been isued in 1864, depicting King William III. From 1883, low values had a design based on the numeral of value, while higher values continued to portray the monarch, which from 1892 was Queen Wilhelmina.

Not until the 1930s did native scenes began to get a look in. Even then, these were very much of a colonial nature, usually aiming to glorify the goodwill of the Dutch towards the indigenous population.

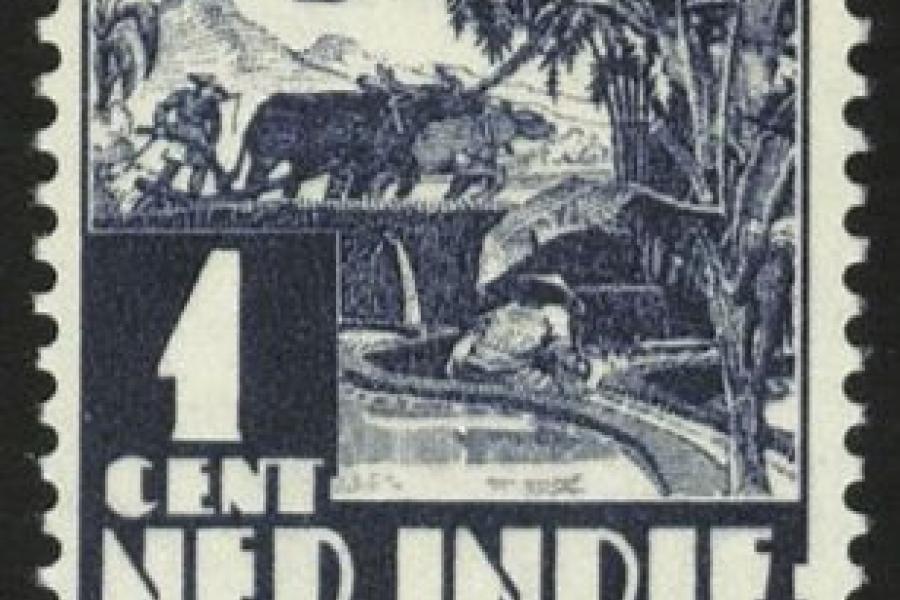

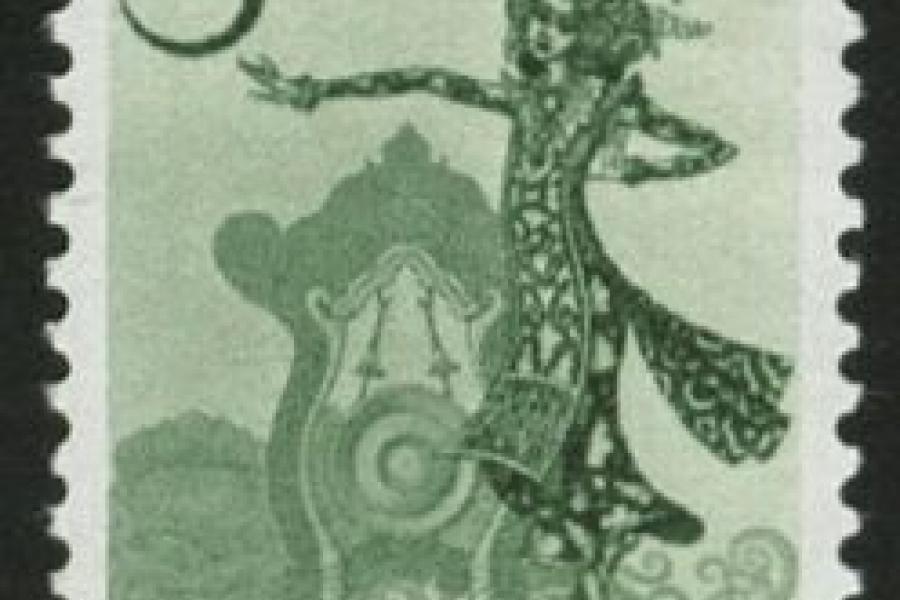

Charity and welfare issues were joined by low-value definitive designs showing rice cultivation with the aid of buffalo, from 1933, and native dancers, in 1941.

Japanese occupation

World War II changed everything. Desperately in need of new sources of raw materials after going to war with the USA, Japan attacked the Netherlands Indies for its gas, oil and rubber resources in January 1942.

The Netherlands itself, under German occupation, was in no position to defend its colony, which capitulated within a week. Some 40,000 troops, and many Dutch civilians, were interned.

Indonesian nationalists, however, saw an opportunity in the occupation, and started to make overtures to the Japanese. These were condoned, as long as they did not interfere with the war effort.

Even the Dutch government in exile in London realised that its eastern colonies could never be liberated without American help, and that it would not be allowed to re-establish old-style colonial rule, so it started to ponder ways to grant the Indies some form of post-war independence within the kingdom.

Stamps of 1941-45

As with other countries under Japanese occupation, this is a very complex period to collect.

The Japanese divided the Netherlands Indies into three areas: Java, Sumatra, and Borneo & The Great East (which included Sulawesi, the Moluccas and New Guinea).

Only Java received new stamps throughout the occupation, with a First Anniversary of Occupation set in 1943 followed by two others depicting local scenes.

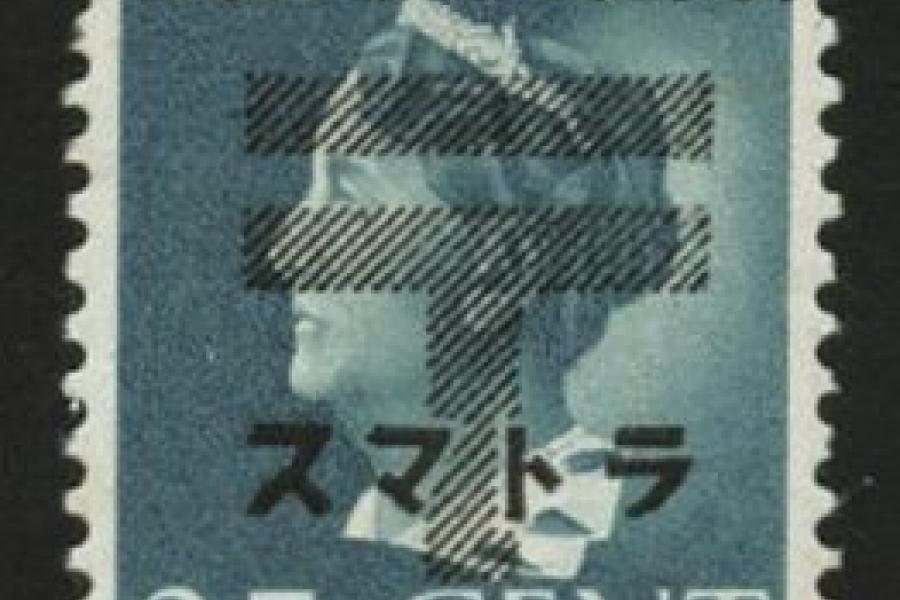

Both Sumatra and Borneo also got new definitive stamps in 1943, but otherwise used overprints of existing stamps from the Netherlands Indies, Japan and Malaya.

The Borneo administration kept things relatively simple by mainly using the so-called ‘anchor’ overprint, albeit in numerous varieties.

Sumatra started off with provincial overprints in dozens of different types and colours. These were followed by the so-called semi-general overprints, consisting of a single line of Japanese text, and later by general overprints, which had two lines of Japanese text plus bars to obliterate the face of Queen Wilhelmina; superstition dictated that she should not be allowed to stare at the Japanese from off the mail.

These overprints were initially applied by hand, and subsequently by machine.

Just like the old days

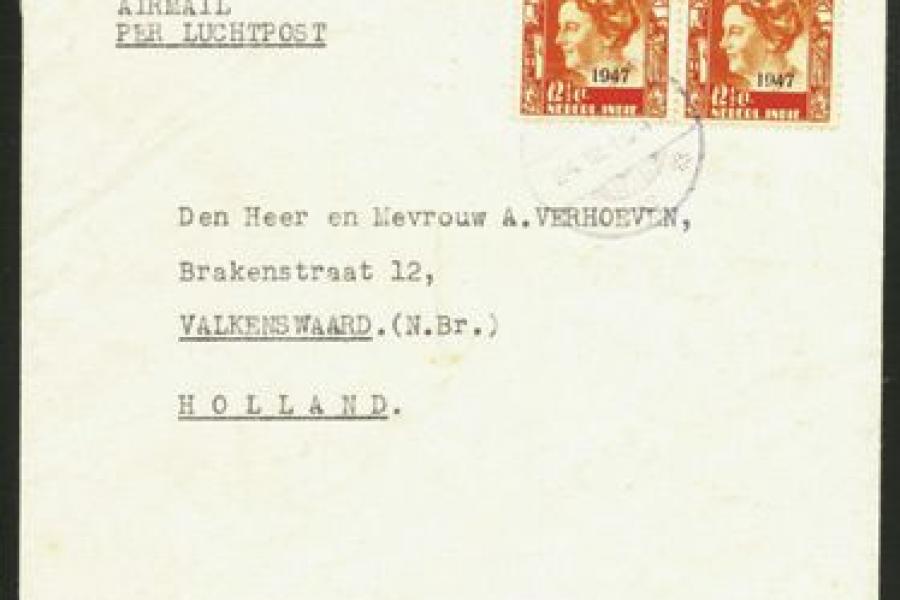

Once the war was over, Dutch rule was readily restored in the areas which were under the control of American and Australian forces. The old stamps bearing the Queen’s portrait were reintroduced, although this was something of a propaganda blunder as it looked like part of a plan to simply re-establish colonial power.

When some stocks of stamps fell into the wrong hands, new stocks were overprinted ‘1947’ to validate them, but still the Dutch clung to their colonial-style designs.

Rise of the republic

In Java and Sumatra, meanwhile, the Dutch failed to regain their authority because revolution broke out. On August 17, 1945, just two days after the Japanese surrender, Sukarno and his right-hand man Mohammad Hatta declared their country’s independence as the Republic of Indonesia.

British troops, under the command of Admiral Mountbatten, were sent in, but political sensitivities caused them to withdraw as quickly as possible.

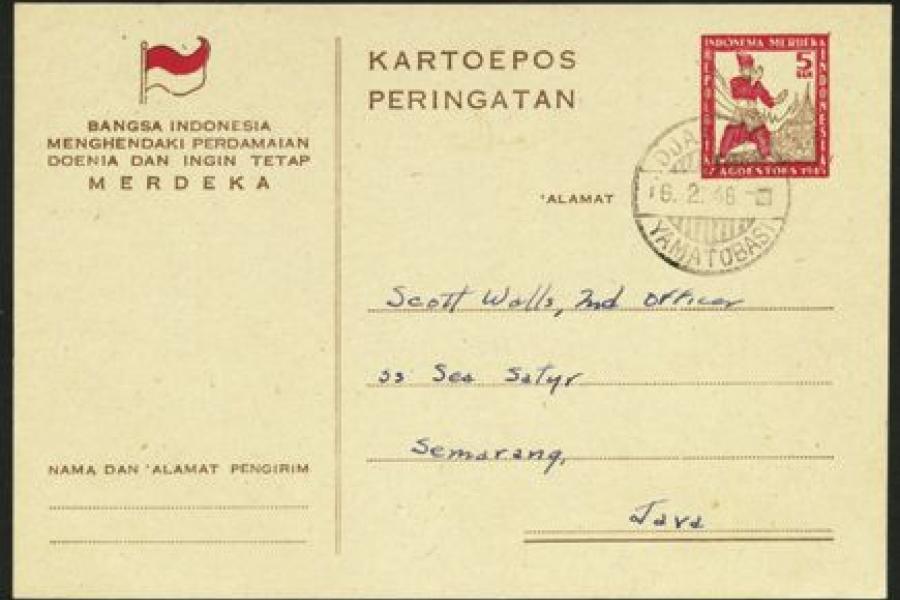

The Republic first used up existing stocks of stamps with Japanese overprints, applying their own overprints on them. These mainly consist of ‘Repoeblik Indonesia’ in various guises, including abbreviations.

In late 1945 came the first new issue, celebrating the declaration of independence with two different designs depicting a bull, which can be found perforated or imperforate. This was followed by three sets in 1946.

Disunited states

It was not until the end of 1946 that the Dutch government managed to formulate a declaration on the future of the islands. It hoped to establish a democratic United States of Indonesia (one of which would be the Republic), arranged on federal lines but with the Queen remaining head of state.

The Linggadjati Agreement was drawn up between the Dutch and the Republicans in March 1947, but further negotiations ran into a brick wall of irreconcilable differences.

The Dutch authorities then launched a series of ‘police actions’, supposedly to root out malicious elements within the Republic. To the eyes of the world, though, this looked very much like military intervention to reoccupy a former colony.

The United Nations intervened, and the USA threatened to withhold Marshall aid to the Netherlands, forcing it back to the negotiating table.

Birth of a nation

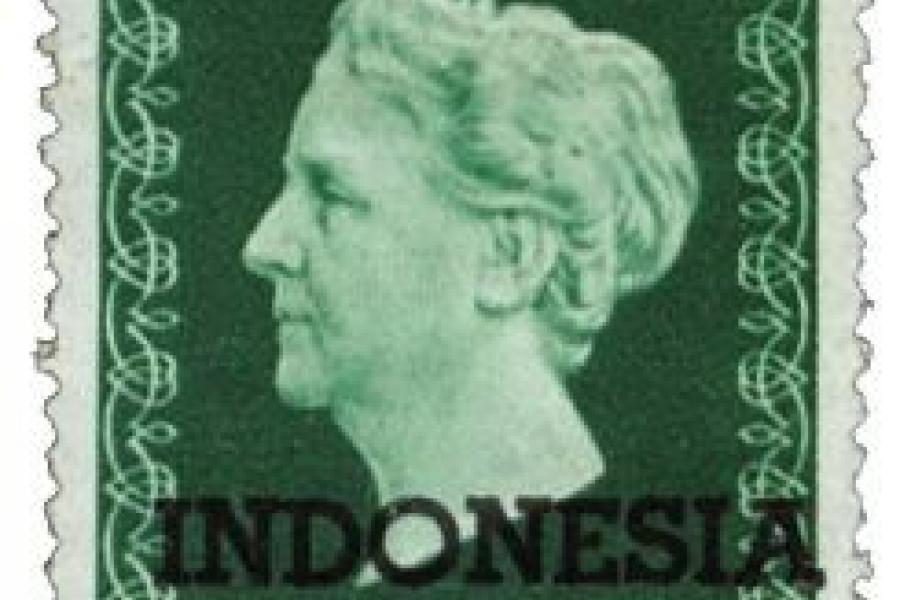

Full independence finally began to look inevitable, and in September 1948 the country was officially renamed Indonesia, anticipating a subsequent transfer of sovereignty.

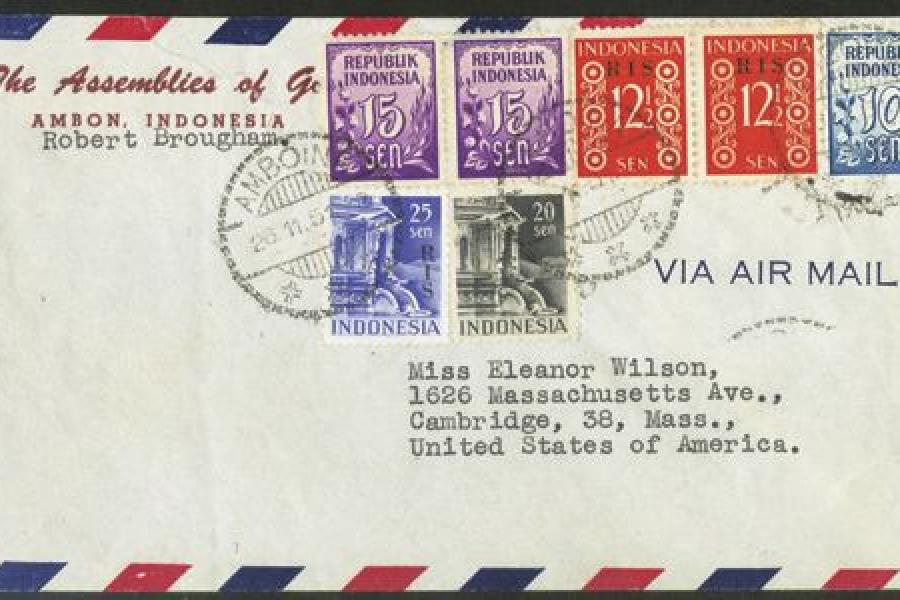

Existing Netherlands Indies stamps ranging in value from 15c to 25g were reissued with the old name obliterated and ‘Indonesia’ overprinted.

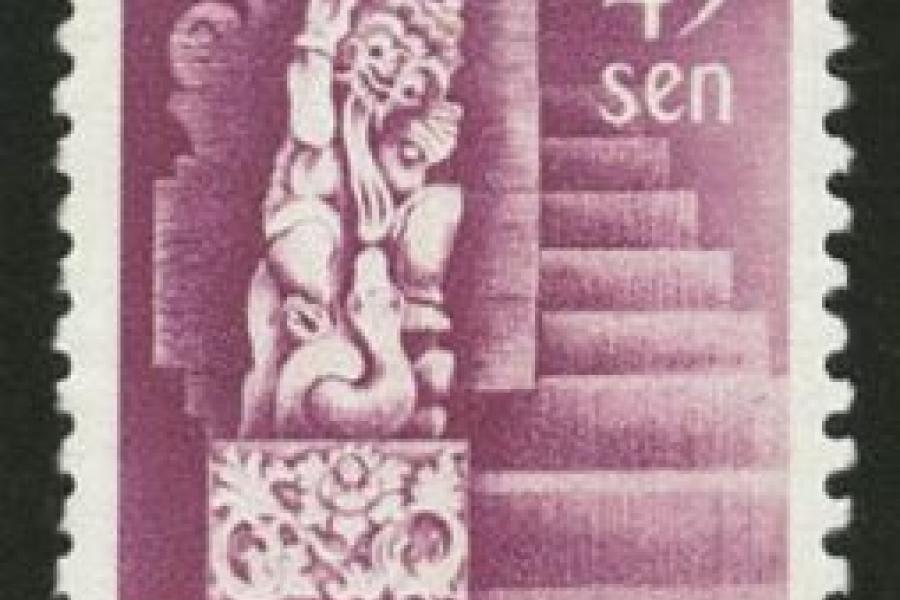

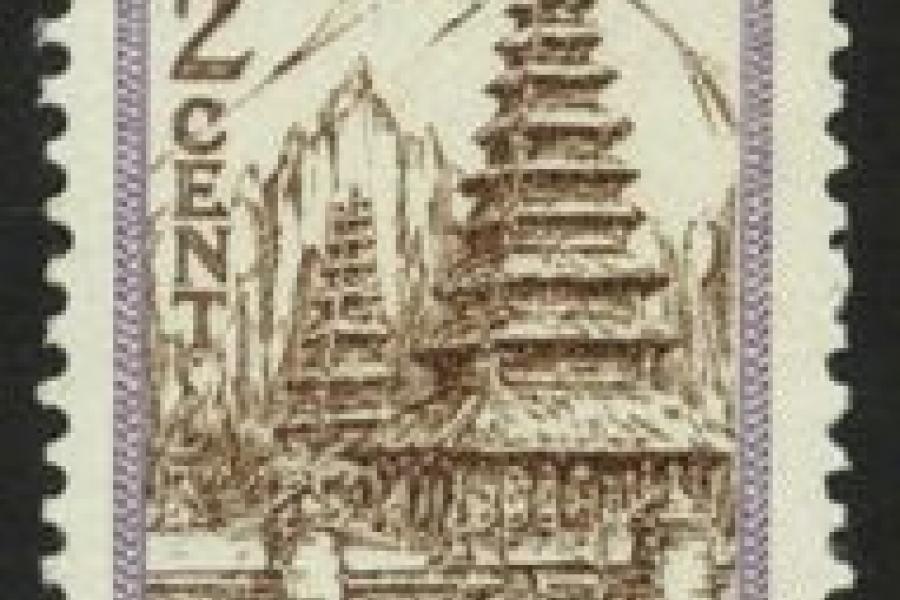

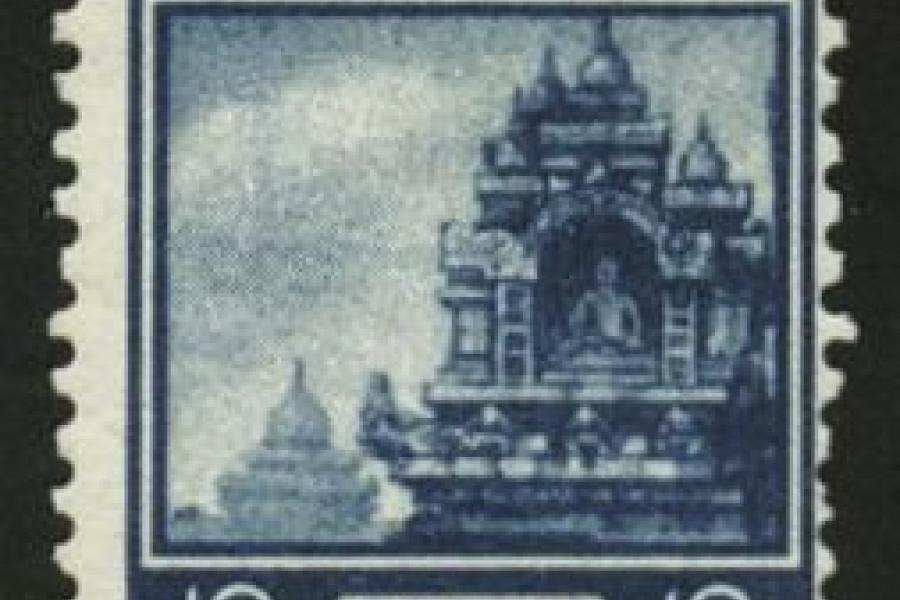

For 1949, a new set of definitives was issued, with the new country name, a new currency of sen and rupiah replacing cents and guilders, and no royal portrait. The lower values had the denomination prominent, while the higher values illustrated the portal of the temple of Tjandi Poentadewa.

On December 27, 1949, the Dutch government finally transferred the sovereignty of the Indies to the Indonesians, with the exception of New Guinea, which would remain a Dutch territory until 1962.

Rapid transformation

The United States of Indonesia would have a short lifespan.

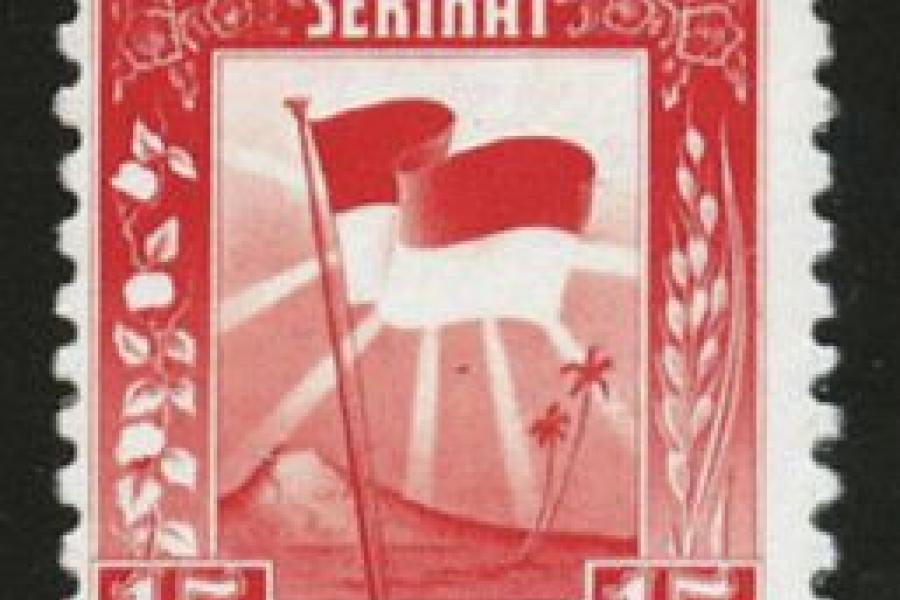

It produced just one special stamp issue, showing the national flag and inscribed ‘Republik Indonesia Serikat’, to mark its inauguration. Besides this, there was time for only a series of ‘RIS’ overprints on the 1949 definitives, before the federal state was dissolved in April 1950.

It was replaced by a unitary one, with Sukarno as its increasingly authoritarian President and stamps inscribed ‘Republik Indonesia’.

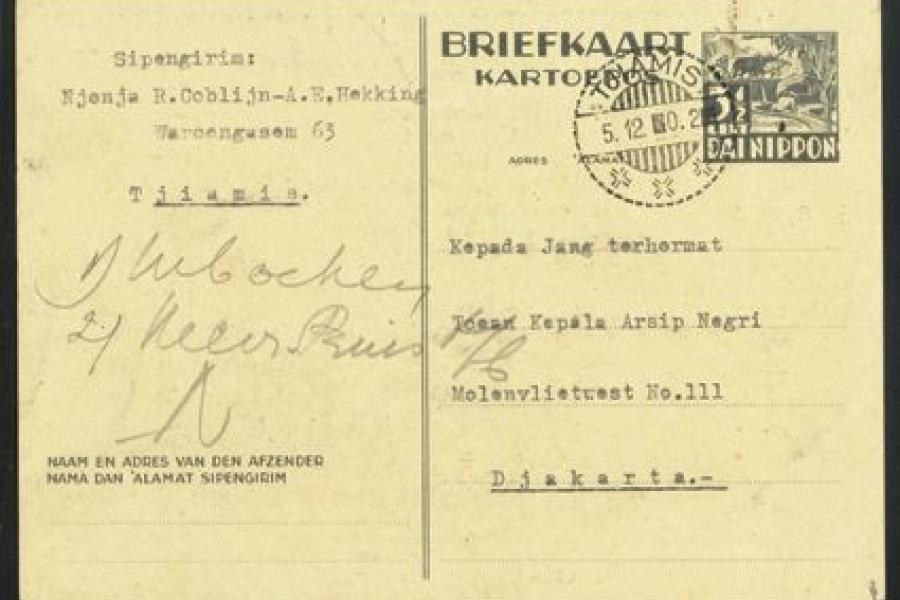

Japanese occupation postmarks

When studying the postmarks of the Japanese occupation period, note that different calendars were used. They are the western Gregorian calendar, which was in use before the occupation, and two Japanese calendars: the Koki calendar which starts in 660BC, and the Showa calendar which starts in 1926. The table below shows the various years which may be encountered.

Showa postmarks show the year first, then the month, then the day. Koki postmarks, like Gregorian ones, show the day first and the year (usually with the first two digits omitted) last.

A fourth type is the Teikuko Seifu cancel, which is dateless.

Gregorian year 1942 1943 1944 1945

Koki year 2602 2603 2604 2605

Showa year 17 18 19 20

Two series of unofficial stamps emerged from republican areas in the 1945-49 period.

The so-called ‘Vienna printings’ (actually printed both at Vienna in Austria and at Philadelphia in the USA) were probably instigated by the shrewd US stamp dealer Julius Stolow and the Indonesian ambassador to the US.

They are found only mint or unofficially used (cancelled to order or sent outside the normal postal channels) and are usually regarded as completely bogus. But they were actually for sale in post offices in Indonesia for a very short period, so perhaps that is too simplistic a description.

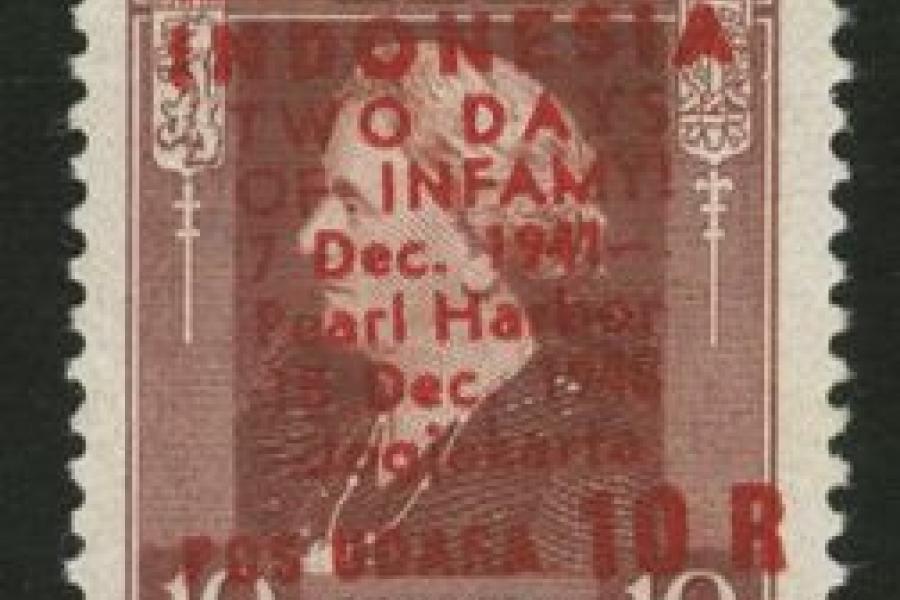

The so-called ‘Infamy overprints’ on Netherlands Indies definitives, on the other hand, were an obvious propaganda stunt, trying to sway American opinion in favour of Indonesian nationalism.

Again, they were the work of Stolow, the overprints referring to ‘two days of infamy’: the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and Dutch military intervention in Indonesia 1948.